Emily Kling is a Cohort 8 Seton Teaching Fellow serving at Romero Academy at Resurrection in Price Hill, Cincinnati. She attended the College of Saint Benedict in St. John’s, Minnesota where she studied Theology. In this short piece, read Emily’s reflection on rest, and how God has revealed to her the nature of rest in the modern world not only through her own academic study of our faith, but also her through work with her disciples as a Seton Teaching Fellow.

My disciples are captivated by stories. One familiar example is the story of Jesus rebuking the storm in the synoptic Gospels. Despite the engulfing waves and frantic disposition of His disciples, the Lord is unstirred, asleep in the sinking boat before He is suddenly woken by the worried disciples. With the Lordship of his words, Jesus immediately stops the torrents of water that threatens them. “What kind of man is this? Even the winds and waves obey Him!” He is the Lord – the Alpha and Omega, He who was and who is and who is to come. Jesus is the King of the Universe and yet he rests. There is simultaneously an oddity and fittingness to a God who rests.

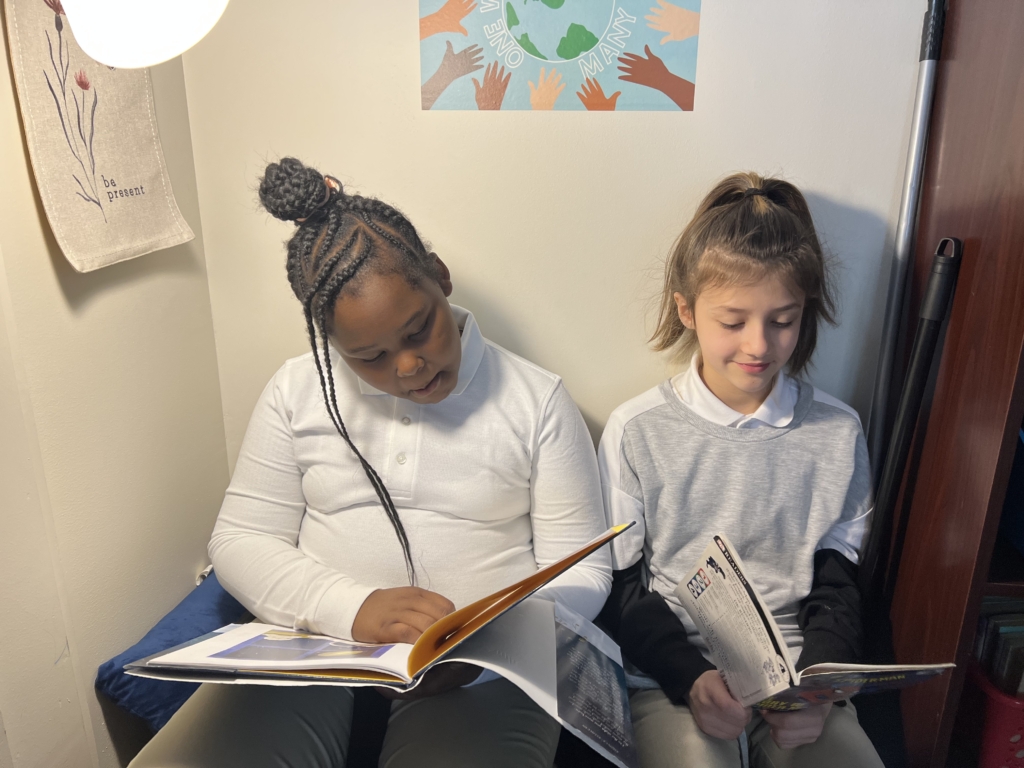

If there is one thing we value, it is efficiency. However, having the efficiency of a machine is not and cannot be the standard of our human flourishing. We are not good humans only to the extent that we push our minds and bodies to capacity or to eventual collapse; this is an irresponsible use of our freedom, which is not conformed to our destiny. We possess a supernatural destiny which profoundly alters the way we interact with reality. My students cannot be reduced to a sum of accomplishments or test scores; they are children to behold, not problems to be solved. Instinctively, we know that some things are meant to be marveled or known for their own sake, not glanced over and my students are no exception. If we are to appreciate life to its depths, we must enjoy time and not merely use it.

Why does God rest and how does rest alter the way humans ought to interact with reality?

The answer is found in creation. The Lord saw it fit to punctuate the day with intention—with appointed times of work and rest. The celestial patterns of the sun and moon obey their Creator with their rising and setting. Birds, fish, and mammals utilize the night and day to delineate their activities for survival. Human beings abide by the same principles of work and rest set forth by God because we are rational beings fashioned in His image and likeness

Since the creation story in Genesis is an account of God’s creative action and rest, each day is episodic but nonetheless purposeful. Here, God is wholly dynamic as He creates from nothing and instills order within the formless void by a single divine utterance. The Lord designates the Seventh day for rest not out of any divine privation—as there is nothing lacking in God that is proper to His nature—but to model for us our human need for the Sabbath.

What is true rest or leisure?

The Sabbath compels me to humbly revisit this question each week. Examining this question and recognizing the need for leisure takes courage. The modern mindset defines leisure as merely a break from work, in which one is untethered to all obligation and thought of obligation. On the contrary, the Catholic notion of true rest is more full because our minds contemplate the one thing necessary: God. It requires humility to reclaim leisure as a restorative activity aligned with our spiritual nature, not a guilt-ridden pastime. Instinctively, we know that the purpose of human activity is more than just labor or work because our reason is ordered to the practical and speculative—to work and rest.

Our modern sensibilities are becoming less and less aligned with our spiritual needs. The main pursuit involves impressing our mark upon the world and making or using external things—the cult of efficiency. This mindset has eased its way into my missionary year, as it is tempting to be overly preoccupied with efficiency over my community relationships or spiritual needs. The constant need to be accomplishing something is damaging, even if it means accomplishing something good like lesson planning or grading papers.Although my classroom instruction is necessary, I can easily crowd out the time for prayer and leisure that my students need. Recently, I have begun incorporating designated times of prayer during class—to be truly present to the Lord. I want my students to know that it is good to “waste time” with the Lord because He is worth delighting in simply for His own sake. Instead of viewing leisure as merely a superfluous activity, I must learn to view it as an integral activity of the spiritual life. Leisure is restorative to our minds, bodies and souls because the Lord ordained it to be truly good and essential for humanity. When we make time for leisure, we affirm the goodness of our place in the order of creation—that we are immersed in and ordered toward contemplative union with God, in which we find true rest.