How do our scholars develop a “growth mindset” and why does it matter? According to the research conducted by Carol Dweck, the psychologist who made this term well known, “students’ mindsets—how they perceive their abilities—played a key role in their motivation and achievement, and we found that if we changed students’ mindsets, we could boost their achievement.”

Dweck goes on to explain that one of the primary ways educators can impact a student’s mindset is through instruction that encourages them to believe their intelligence is not fixed but can be changed—that they can “grow their brains.”

Meaningful and consistent feedback is one of the most important instructional tools for developing the kind of mindset that fosters both student motivation and achievement, and it’s an artform Seton Education Partners seeks to develop at all levels—among our scholars, families, staff, and leadership.

To foster this ability to receive and incorporate feedback in our students, we invest them “in their specific goals so that they know exactly what they need to work on in any given lesson or day,” explains Molly Rippe, Assistant Elementary Superintendent for Brilla Schools Network. “You will often see scholars with goal cards on their desk that help to serve as reminders of what is expected of them. During independent work time, teachers actively confer with scholars to give them transferable feedback that they can apply not only to the skill or task being assessed that day, but future learning, too! In that way, we use feedback to stamp key learning and highlight transferability.”

It’s also important that teachers, especially those new to the classroom, are given the space to develop a mindset that welcomes opportunities for growth, rather than viewing feedback as a potential threat that judges whether they are “good at teaching” or not.

Emily Brooks, Senior Director of Instructional Coaching, shared a story of how a more novice teacher was frustrated by the degree to which her scholars were chatting during lessons at the beginning of the school year. This is how they found a solution:

“I asked her more about the situation she was encountering, in hopes that by taking the dedicated time to reflect on the root cause of the challenge, she could then tap into her own genius and determine how to move forward. Through some back and forth, this teacher identified an exact moment where her procedures were lacking (when scholars transitioned back into the classroom from another setting) and how this was leading to increased side-chatter, and how this then trickled into her lessons the rest of the day. The teacher then identified some strategies to meet this pedagogical challenge, and collaboratively we picked one bite-sized strategy (“threshold”) she should focus on immediately. Together, we scripted and practiced, being sure to highlight where her other instructional strengths could support this area of growth. Finally, I told the teacher I would come in to support her as she tried the new strategy. On the following day, I observed this teacher implementing the feedback. She was successful in executing her new routine and ultimately, the larger problem of scholars being chatty during her lessons was greatly minimized. The teacher also seemed more joyful and confident while teaching!”

Notice that Brooks did not simply give this teacher some instructional suggestions and walk away. Together, they reflected on and discussed the challenge in detail, found one small strategy to implement, practiced and observed it in action (which led to even more feedback), and then celebrated this teacher’s success.

Is this novice teacher likely to view honest feedback as a threat to her abilities or worth as a teacher? Not a chance!

Is this teacher likely to adopt similar strategies when it comes to helping her own scholars work through academic or behavioral challenges? Absolutely.

While Brilla also uses written feedback rooted in a Teacher Evaluation Rubric, “live coaching” is a priority. “As a network, we are emphasizing live coaching so that teachers are urgently getting and responding to feedback in real time,” explains Rippe. “We’ve found that this teacher action helps to move teacher practice much more quickly than a typical observation and feedback practice.”

Brilla’s “Teach Back” is probably one of the best ways the network develops and models the art of feedback. “In this protocol,” says Rippe, “teams practice a specific lesson together, usually with one of our instructional leaders in the room. They take turns teaching a portion of the lesson, with others acting as scholars would in order to create the most authentic experience, and then give one another feedback before trying it again. Doing this routinely helps to make everyone feel comfortable with giving and getting feedback and makes the quality of the lessons much stronger. It’s fun to see how these evolve over the course of the year. At the beginning of the school year, a team member might be hesitant or give vague feedback, but once they see the impact of applying Teach Back feedback in their actual lesson, they immediately see the value and the quality of the feedback they give likewise improves.”

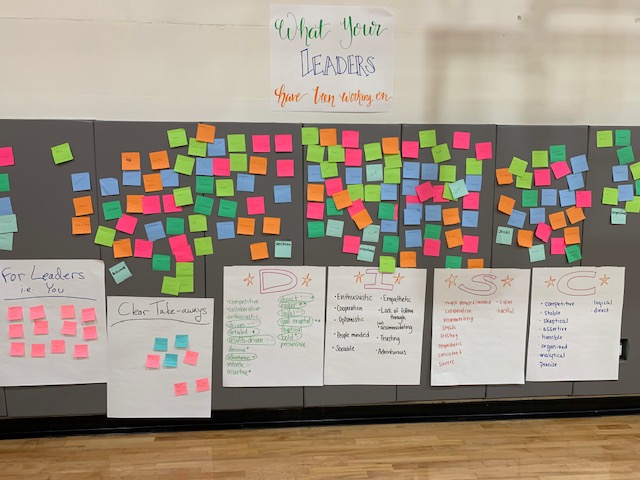

Another important component of meaningful feedback is making sure that those who take the time to provide it know that it is being received and thoughtfully considered. A good example of this receptivity and follow up is Brilla’s recent Staff Onboarding in the Bronx. After staff had the opportunity to give feedback on the onboarding experience, Jen Gowers, Brilla’s Chief of Schools Management, Instruction and Professional Development, responded with a series of emails directly addressing any constructive feedback staff had provided. Consider these examples from Jen’s follow-up:

- Co-Teaching was rated 100% uplifting to the young people we serve; 80% beneficial and effectively, engagingly facilitated; 60% immediately implementable. Heard! It sounds like we’ll need more practice and development to ensure this can be enacted with excellence. Comments indicated folks especially appreciated learning practically about the IEP process and indicated concern regarding having enough exceptional speech providers for our young people.

- 90% of you thought Opening Routines was engaging, beneficial, uplifting to those we serve and to Brilla Overall. 95% of you benefited from and can see the impact of the DiSC session. 100% of you thought DiSC Archetypes was engaging, beneficial, uplifting to those we serve and to Brilla overall. 99% of you thought Values was a super powerful session. 90% of you thought Influencer Model was helpful. And in a SLAM DUNK, 100% of you agreed or strongly agreed that Dignified Accountability was engaging, beneficial, uplifting to those we serve and to Brilla! Overall, you wanted more practice and more feedback. We heard you! <3

Notice how constructive feedback is both recognized and phrased as an opportunity to learn and grow, not as a “failure”—this way of communicating is how we develop a growth mindset in ourselves and also model it to scholars and colleagues across our schools.

Finally, frequently asking the families of our scholars for feedback is another important aspect of our approach. At Brilla, “families are asked to formally give feedback on the school three times per year. These surveys ask families to reflect on their experiences with their child’s teachers and the school overall. We look at these results and analyze them with the school leadership teams to be responsive to family needs and experiences. Outside of these formal surveys, we always invite family feedback through our Family Involvement Committees and during parent events. Especially now, we want to ensure that our programming is constantly adapting to the needs of our families.”

Constantly adapting. Responding in real time. Practicing and implementing.

These are all actions that foster a mindset of openness, dialogue, and growth in our schools, impacting the culture of learning at every level. Such a robust approach also models to students the vital artform that is giving and receiving feedback, a skill that will impact not only their academic achievement, but many other areas of their lives.