Jack Morgan was a Cohort 8 Seton Teaching Fellow. He taught third and fourth grade in the South Bronx, New York City at Brilla Veritas elementary school. Jack stayed on with the mission and currently recruits Seton Teaching Fellows with the network team. Jack is a convert to Catholicism, and during his year as a missionary, he encountered the beauty and power of prayer with his disciples and community. In this piece, Jack reflects on the true crisis facing the modern church: a loss of the special grace that is the gift of mystical prayer.

I spent the last year of my life serving as a Catholic educator. I also spent a fair amount of time on the internet, and being a Catholic, there was certainly a religious bent to my internet searches. The thing is, if you spend time on the Catholic corners of the internet, you’ll inevitably find a lot of parties claiming to know the biggest problem facing the Church today. Some say poor clerics; others mention society’s general decline in morality; many the creeping of modernism and progressive ideologies into the Church and our educational institutions; and there are a host of other supposed concerns that follow. While all of these topics are issues to be addressed by the Church faithful, I’ve come to realize that these are all symptoms of a much larger problem–and it’s a problem I experienced while I served as a catechist and missionary. Namely, the reason that our Church is in a time of crisis is because, before all other things, we have ceased to be a people of prayer. In other words, we have ceased to be a mystical people.

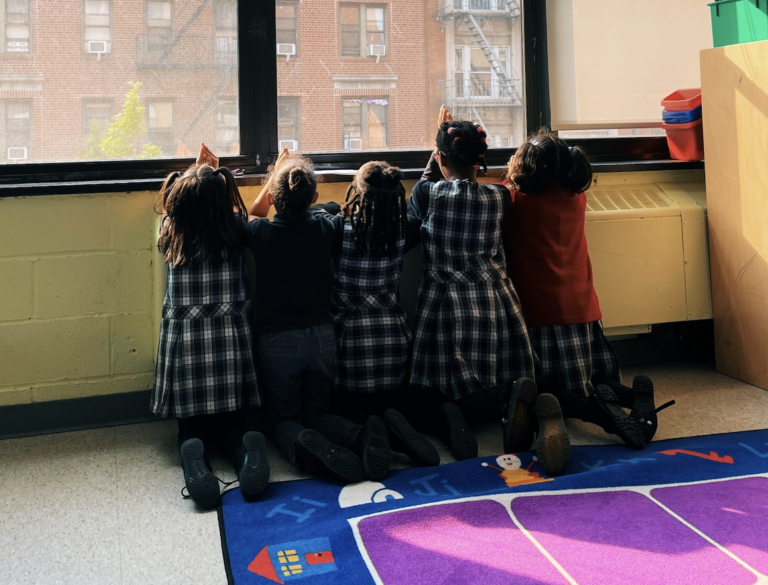

We who are faithful Catholics often know just how to teach the finer points of dogmatic theology–from morality to the sacraments; however, few Catholics really know how to embark upon the path of prayer. There are even fewer who have spent time considering how they might teach others to embark on this path and it translates to the way we educate young people in the faith. The reality is, we as Catholic educators have to do more than just teach the intellectual side of Christianity, and we need to do so for the sake of the Church and her sheep. As educators, we should ultimately want the next generation of Catholics to be categorized by their mystical encounters with the Living God rather than their astute knowledge of the faith alone.

On this fundamental quality of Christianity, Abbot Nicolas of Holy Resurrection Monastery says, “Christianity is a mystical religion.” In essence, mysticism is participation in a mystery, so its true depths cannot be contained in a literal definition. However, the Church’s Catechism can help us a great deal in understanding what mysticism involves: “Spiritual progress tends toward ever more intimate union with Christ. This union is called ‘mystical’ because it participates in the mystery of Christ through the sacraments—‘the holy mysteries’—and, in Him, in the mystery of the Holy Trinity. God calls us all to this intimate union with him, even if the special graces or extraordinary signs of this mystical life are granted only to some for the sake of manifesting the gratuitous gift given to all (CCC Paragraph 2014).”

As educators, we should ultimately want the next generation of Catholics to be categorized by their mystical encounters with the Living God rather than their astute knowledge of the faith alone.

This gift is a share in the inner life of God Himself. Sounds lofty and indefinite, doesn’t it? Excellent, but what does it mean to “share in the inner life of God?” In the West (which for the sake of this example simply means those parts of the world influenced by the cultural outgrowth of the European Enlightenment), we have come to reject anything we cannot fully grasp in a physical or intellectual sense. If we are given the option between two conceptions of reality, we tend to choose the one which makes the most sense for us and seems (to our senses) more certain. However, what is most certain is not always preferable or even practical. In fact, all of us are required to exercise a level of trust in that which is unknown to us or unexplored; even things which are ultimately not fully comprehensible. This is what we call faith.

Think of someone you love and whom you believe loves you in return. There is no way to truly know if somebody loves us; that the feelings we have for the other are mutual. There are certainly signs and tangible experiences of love, but we can’t have a scientific grasp of another’s heart. We are not psychics; we cannot read the mind of another or examine the inner workings of their hearts. We have to have faith that their love is true.

If we only trust what is knowable to us, we run the risk of paralysis and if we allow this line of thinking to run its course to its furthest conclusion, we ultimately reject life itself. Taken to the extreme: I can’t physically prove in the moment that the water I am drinking won’t somehow suddenly turn into arsenic or to know with absolute certainty that my computer won’t electrocute me. I have faith based on my experiential knowledge of the water I am drinking and the computer I am typing on that these will not happen. I do this specifically because I have experienced these realities. Along this line of thinking, God’s love is a seemingly difficult thing to show if you rely entirely on physical means of knowing, and that is precisely the importance of a mystical experience—it informs our faith through an experienced reality.

Let us return to the catechism’s discussion of mysticism: “Spiritual progress tends toward ever more intimate union with Christ. This union is called ‘mystical’ because it participates in the mystery of Christ through the sacraments (Latin word for Mystery)—‘the holy mysteries’—and, in him, in the mystery of the Holy Trinity.” So this mystical union extends beyond Christ. It encompasses all the persons of the Holy Trinity. This has a Scriptural basis. Christ says in the Gospel of John that “eternal life is this: knowing God the Father and Jesus Christ (Jn. 17:3).” In this case knowing does not refer to abstract knowledge but experiential knowledge. This knowledge is the same type the author of Genesis speaks of when under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, he wrote that “Adam knew his wife Eve (Gen. 4:1).”

It is not surprising that the most accurate analogy for the spiritual life is that of the wedding of one’s soul with Christ. This is a narrative which permeates the entirety of Scripture. Israel is the bride of YHWH. The New Israel, the Church, is the bride of Christ. Why? Because the Christian understanding of marriage is that the bride and bridegroom become one flesh through marriage; “they are no longer two but one.” In a mysterious way, a wedded couple become one and share their life with one another. This is beautifully modeled in the sacrament of marriage. This is a reality that is meant to symbolize and actualize the reality of the deeper and intimate union between their souls. Therefore, it also is fitting that God is referred to as the bridegroom (the man) and the Church as the bride (the woman) because God is the initiator of this union.

So, God has created us to enter into mystical union with us; to pour His love into our hearts (Romans 5:5). He continually stands at the door of our hearts and knocks. He reaches out in His incarnation, Christ, who has come that we might have “life and have it to the fullest” (Jn. 10:10). Our existence is most fundamentally realized when we enter into deeper union with God. But what happens when we are never taught how to open up the door? What if we don’t know how to engage in union with God? This is the true root of the crisis we are facing: we don’t know how to know God. Our crisis exists, as Edward Kleingeutl puts it, because “many have lost or have not been exposed to one of the fundamental components of the spiritual life: the ability to encounter Jesus through prayer.” We as a Church and society no longer know how to pray as we should.

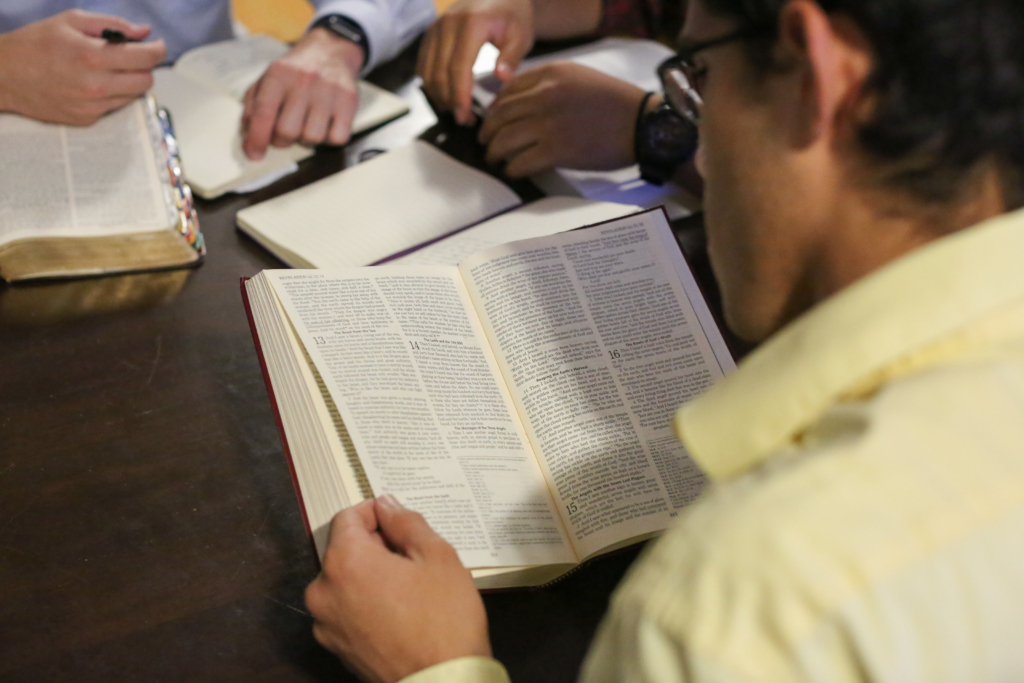

Think of yourself and your spiritual life, and then compare that to the holiest person you know (or at least know of). What is the difference between you and them? It cannot be simply how much they academically know about the faith. If so, St. Teresa of Avila and St. Therese of Lisieux would not be saints. However, these two holy women are in fact saints, despite a lack of academic knowledge, because they are in fact true theologians: they have experiential knowledge of God. There is an old adage in Christianity: “He who truly prays is a theologian, and he is a theologian who truly prays.” The early Church’s understanding of theology was always connected to prayer and experiential knowledge of God. If you had a question about God, you did not go to somebody with a degree in theology. You went to the monk or nun living in the wilderness. If you sought God, you didn’t go to an academy to learn about him. You fasted. You prayed. You studied Sacred Scripture in a prayerful manner. We’ve lost this sense of knowing God.

We understand God when we encounter Him through prayer, not vice-versa.

Contrast this with our modern attempts at catechism. How many theology and catechism classes have you attended or witnessed where the most they encouraged you in your life of prayer was to say a rosary or an Our Father? Worse than that, how often is the encouragement merely to say these prayers, rather than showing children why and how prayers are to be said, and how to find the beauty of prayer in an experiential way? We believe that children’s’ time for contemplative prayer and mystical encounters are in the future, not in the present. We tell ourselves that they need to learn more and understand more before they can really find God in prayer. The thing is, it’s quite the opposite. We understand God when we encounter Him through prayer, not vice-versa.

When I served as a Seton Teaching Fellow, I often found myself reflecting on my catechism classes, and I would find myself despairing and lamenting the lack of knowledge my disciples (who are young children) had about the faith. I thought I needed to correct every misconception they had about God before they could even begin to encounter Christ truly in prayer. But God had to humble me. I had to ask myself, is this the case? Did God wait for me to correct all of my faulty ideas about Him before He allowed me to encounter Him mystically through prayer? No. God comes to meet us. He does not leave us downtrodden and forsaken. He is the one who extends His fatherly hand as we, much like Adam in the famous painting by Michelangelo, try to reach out to him imperfectly. And he gladly meets us in our imperfections.

This article is a chance to draw attention to something that we are lacking within the Church. I don’t have all the answers to this problem, just some suggestions. This story, I hope and pray, can at least help to inspire the body of Christ to dream again; to consider how we can hand on the Faith–the living and experiential faith–to the next generation. If I was to offer some wisdom, two suggestions come to my mind as possible beginnings in the search for how we can teach our youth—and the Church as a whole—to encounter Christ in prayer once again. First, we must relentlessly pursue Christ in prayer and fasting; we must become warriors in spiritual combat. Second, we must seek the counsel of the saints living among us.

To the first point, pursuing Christ relentlessly through prayer and fasting (as well as other ascetic practices) is not an option. We must believe, like G.K. Chesterton, that the problem with the world is ourselves. As Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a Soviet prisoner, once said, “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being (28, The Gulag Archipelago, Collins 1974).” We ourselves are tainted by the effects of sin. We ourselves contribute to the evils of the world. We ourselves are solidifying problems within the Church.

Only through fasting (the doorway to love by the denial of self-will) and prayer (the means of union with Christ) can we throw off the shackles “of the sin which so easily entangles us” (Heb. 12:3) to be able to “remove the speck from our brother’s eye” (Mt. 7:5). How can we expect to lead our spiritual children and our brothers and sisters in Christ if we ourselves have a plank in our own eye? That is the definition of the blind leading the blind (Mt. 15:14). So, our first step is to renew our baptismal vows through a deeper devotion to Christ in fasting and prayer.

The second point, seeking the council of saints, is self-explanatory. The people who have the answer to our modern dilemma are not necessarily the Catholics who hold doctorate degrees in theology, but those who know Our Lord the most intimately (though these two states are not mutually exclusive). They themselves who pray mystically walk this path. These Christians know the way. We must follow them. We must rely on them to supply us with the wisdom to renew the Church’s life of prayer. It is much easier than we suspect to find the holy men and women of our time. It’s a simple response, but, if you don’t know where to begin, pray for God to show you.

As a former catechist, I have to address this prevalent fault in education. The reality for Catholic educators is that we must do better. The Church depends on it. Our own salvation depends upon it. When we stand before God, we will give account for every deed we did and every deed we failed to do. We should be motivated to stand before him in joyful victory, knowing that our example of prayer and mystical love for Christ was shared with the others. Let us take action and leave no stone unturned in our pursuit of spiritual renewal in the Church, so that we can see the next generation on fire for our faith and one day hear those hallowed words: “well done my good and faithful servant.”